Citizen Diplomacy in a Changing World

John W. McDonald

Ambassador, ret.

Institute for Multi-Track Diplomacy

Extraterrestrial

Civilizations and World Peace Conference

Sponsored by

the Exopolitics Institute

Kailua-Kona Hawaii

10 June, 2006

Aloha,

I graduated from Roosevelt High School in Honolulu

many years ago and it is wonderful to be back on these beautiful islands. I want

to talk about something a little different than what we have been hearing over

the last two days. I want to tell you about

this world in transition and why we seem to be moving the way we are moving, and

I’d like to project what the world might look like at the end of this century.

I

have three theories that I would like to share with you about the state of the

world in 2006. My first theory is what

I call my Empire Theory. Basically,

if you go back over a hundred years in history you will find that the world was

dominated by ten great empires. Today they have all disappeared. After World War

I it was the Ottoman Empire which had been around

for 500 years; then the German Empire and the Austro-Hungarian Empire were gone.

After World War II, the Japanese Empire and then over the next twenty to twenty-five

years the British/Dutch/Belgian/Portuguese Empires, and finally in 1991, the Soviet

Empire disappeared. Now why is this important? Whether it is recognized today

or not: the world that the leaders of these empires ruled, was ruled by fear and

by force. They kept the lid on conflict,

particularly within their own empires.

Today

there is no force out there that can do that or has the power to do that. In 1945 when the UN Charter was signed, every

nation in the world, except Switzerland

which joined a few years ago, signed the Charter. There existed 51 nations in

the world at that time. Today there are 191 nations in the world and Montenegro just

declared independence a few weeks ago and it will become the192nd member by the

General Assembly of the UN in September of this year.

Today

there is no force out there that can do that or has the power to do that. In 1945 when the UN Charter was signed, every

nation in the world, except Switzerland

which joined a few years ago, signed the Charter. There existed 51 nations in

the world at that time. Today there are 191 nations in the world and Montenegro just

declared independence a few weeks ago and it will become the192nd member by the

General Assembly of the UN in September of this year.

Where

did all these new nations come from? They

came from all those collapsed empires. Think about that! Two thirds of the nations of the world today

are less than 45 years old. If this is

not a world in transition, I don’t know what you would call it. Dramatic change is taking place everyday.

My

second theory has to do with conflict, particularly with ethnic conflict.

I was invited to Moscow in 1989 to bring

conflict resolution to the Soviet Empire. I

arrived and I met with members of the Supreme Soviet and within two minutes they

asked to me solve the Azerbaijan-Armenia crisis over Nagorno-Karabakh and I laughed

and I said “I can’t do that”. But I said you can’t do it either because

nobody outside of Moscow

trusts you. They didn’t like to hear

that, but that was true. I said “You

have to find a neutral third party” and they eventually found the Organization

for Security and Co-Operation in Europe. They are still working on that particular conflict.

But

I had their attention by this time and I said “Gentlemen, I estimate that

there are 70 ethnic conflicts below the surface of your empire in 1989, and you

are basically responsible for all of them because you denied three non-negotiable

issues. First thing you required is that

every person in your empire speak Russian. You

did not allow any of these ethnic groups to speak their own language, they had

to speak Russian to survive. The second

thing you did was to deny religion, after all the Soviet Empire was an atheist

empire for 70 years. No religion of any

kind was allowed to be practiced for 70 years.

I

told them that people have fought and died for the right to practice their religion

since time began and I urged them to change the rules. The third non-negotiable issue has to do with

culture. I said you try to deny the ethnicity

of these 70 groups by denying their birth and marriage and death ceremonies, the

clothes they wear, the food they eat, their art, their dance, their music, their

literature. You try to destroy their identity

and they will fight to maintain that identity. I said when you put all three together and you

deny language, religion and culture, you are 100% guaranteed to have conflict,

and killing and death; and you have to change the rules. And the beauty of these three rules is that

they are all man-made. They can all be

changed by the stroke of a pen if the political will is there to do it, and I

urged them to begin that process.

I

told them that people have fought and died for the right to practice their religion

since time began and I urged them to change the rules. The third non-negotiable issue has to do with

culture. I said you try to deny the ethnicity

of these 70 groups by denying their birth and marriage and death ceremonies, the

clothes they wear, the food they eat, their art, their dance, their music, their

literature. You try to destroy their identity

and they will fight to maintain that identity. I said when you put all three together and you

deny language, religion and culture, you are 100% guaranteed to have conflict,

and killing and death; and you have to change the rules. And the beauty of these three rules is that

they are all man-made. They can all be

changed by the stroke of a pen if the political will is there to do it, and I

urged them to begin that process.

The

third theory has to do with the state of the world itself. We’re designed as a world on the basis

of national sovereignty; this was started by the Treaty of Westphalia 350 years

ago. The Charter of the United Nations

is based on national sovereignty. The UN

Charter in Chapter seven deals with International Law when resolutions are passed

dealing with war and peace, and it says that if one nation invades another, then

the UN Security Council can swing into action. The problem in the year 2006 is that the forty

conflicts in the world today are all within national boundaries.

They are intra-state, they are not inter-state. And so we, as a world,

are not designed today, in 2006, to cope with the 40 ethnic conflicts that are

out there. We have to change the way we think and this is a very difficult thing

for nations, particularly nation states, and particularly the United

States, to actually achieve.

Thus,

there is a vacuum out there and what happens when there is a vacuum? People try to fill it in small ways. And so, because governments have been stalemated

and are to this day stalemated, small non-governmental organizations like my Institute

for Multi-Track Diplomacy have begun to move into that vacuum which we anticipate

will be out there for another 15 to 20 years, to see if there is something we

can begin to do to focus on the kind of conflict that the world is enduring and

doing very little about.

In

1985, while I was still with the State Department I wrote the book called “Track

Two” or “Citizen Diplomacy”, the first book of its kind and actually

I had a little problem for publication. This

book outlined eight different actions that individuals had taken to help resolve

conflicts in various parts of the world, on their own, as private citizens.

And my boss, when the book was ready for publication, got cold feet.

He didn’t want a book to come out under a State Department label saying

that there are other and new ways of doing business. So he held up publication

for 18 months. One thing about the Foreign

Service is you always get transferred at some point in time. He got transferred after 18 months, and the

day after he got transferred I got the book published.

In

1985, while I was still with the State Department I wrote the book called “Track

Two” or “Citizen Diplomacy”, the first book of its kind and actually

I had a little problem for publication. This

book outlined eight different actions that individuals had taken to help resolve

conflicts in various parts of the world, on their own, as private citizens.

And my boss, when the book was ready for publication, got cold feet.

He didn’t want a book to come out under a State Department label saying

that there are other and new ways of doing business. So he held up publication

for 18 months. One thing about the Foreign

Service is you always get transferred at some point in time. He got transferred after 18 months, and the

day after he got transferred I got the book published.

It

was a revolutionary document then, and it still is today, in some parts of the

State Department. I am not as optimistic

as one of our speakers yesterday about the understanding of Track One. Track One is government to government, what

I did for 40 years as a diplomat. It is

basically under instructions, it’s fairly rigid, it’s not risk-taking,

and it’s not very imaginative. It

tries to get things done in its own way.

Track

Two Diplomacy” or “Citizen Diplomacy” is person to person, small

group to small group, it’s dynamic, it’s risk-taking, it’s imaginative,

it gets things done that governments are either afraid to do or don’t want

to have to do. I expanded the concept of my first book in 1991 with Dr. Louise

Diamond and wrote a book called “Multi-Track Diplomacy”.

We called it a systems approach to peace.

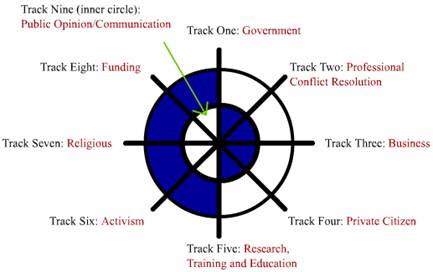

In

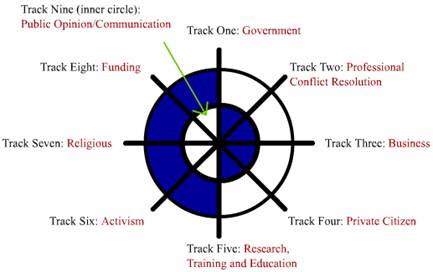

our Multi-Track system, Track One is government, Track Two is non-government.

We expanded the non-governmental aspects into additional tracks. Track

Three is the role of business. A business

can be a powerful change agent, once it takes a long-term perspective about conflict. Track Four is people exchanges, like the Fulbright

Program. People come from one culture,

learning from that culture and going back to their own culture. Track Five is training, education and research

in the field of peacebuilding. That is what we do in the field of conflict resolution.

Track Six is what I call people power, or peace activism.

Track Seven is religion. Track Eight

is money. We are always broke because we

are always asked to do more than we do or have funds for. And then the inner circle, the Ninth Track,

is communication. And that is the heart

of what we are about because we link together everything among those other eight

tracks.

Let

me go back to Track Six for a moment because this shows you dramatically what

I mean when I talk about transition and how fast things are changing. Unfortunately, governments who are not affected,

do not want to hear about this at all. For example, since November of 2003, that’s

just two and a half years ago, eight different nations have changed their political

systems, because of people power. Eight

different nations, collectively, non-violently for the most part, have been able

to change the system and bring about a step toward democracy or democracy itself.

The

first example is the country of Georgia

in the Caucasus. In November of 2003, after a flawed election,

and weeks of demonstrations, people marched peacefully on the Parliament with

armloads of roses, to give to the soldiers surrounding the Parliament. And Shevardnadze, the president of the country,

who was addressing the Parliament at that time, was hustled out the back door.

He resigned the next day and a new government has taken over. It became

called the Rose Revolution.

A

year later, the same thing happened in the Ukraine. In this case, 6 million people demonstrated

in the Ukraine,

to bring about, successfully, change. Then

a few months later it happened in Kyrgyzstan. So three of the former Soviet Empire Nations

are now on a fast track to democracy.

And

then you have Lebanon,

which I am sure many of you have read about recently. Over a million people demonstrated in Beirut. The Syrian government, after 29 years of occupation

withdrew, and they are trying to now build democracy in Lebanon. It has happened in Togo,

it has happened in Ecuador,

it has happened in Bolivia. And just two weeks ago, in the country of Nepal, north of India, 200,000 people demonstrated

against the dictatorial power of the king. The king has relinquished power, and

all power has been passed to the Parliament, which is now actively in session,

trying to rebuild and restart a democracy. So you can see that this is a world

in transition. My guess is that this path

will continue in the years ahead and more countries will go down that same particular

path.

Let

me tell you a bit about what we do in my Institute for Multi-Track Diplomacy and

how we do it. I want these concepts to become universal and to pass into the Universe

itself because they actually do work. I want to talk briefly about three different

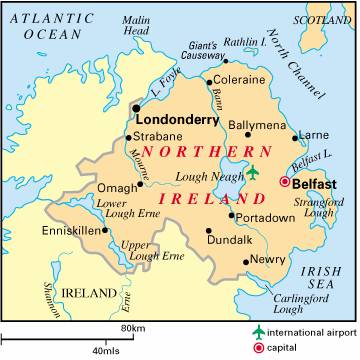

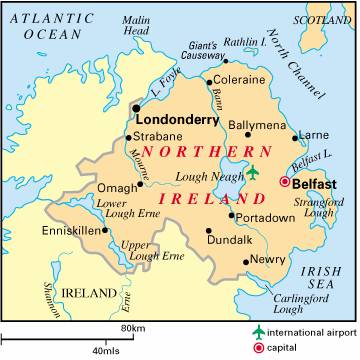

projects that we have worked on through the years as an Institute. The first is Northern

Ireland, the second is Cyprus

and the third is Kashmir. In 1985, the government of the United Kingdom and the government of Ireland signed an International Treaty, dealing

with Northern Ireland

and giving some power to the Catholics, much to the chagrin of the Protestants.

But while I was at the State Department putting on a one day seminar examining

that particular treaty, I was fascinated by one clause in article three. It said that there should be a Bill of Rights

for Northern Ireland.

I was fascinated because neither the United Kingdom

nor Ireland had a Bill of Rights. So why would they talk about a Bill of Rights

for Northern Ireland?

I thought this was certainly worth pursuing so I tried to follow it in the months

ahead to see if anything actually happened.

Well,

nothing seemed to have happened. I retired

from the State Department and became a law professor at George Washington

University and then was invited

to become the first president of the Iowa Peace Institute in 1988. At the end of 1989 I was in London and I went to call on one of my friends

at the Foreign Office who had been involved in that treaty negotiation. I asked

him if something had happened that I missed

regarding the implementation of this Bills of Rights idea which I thought was

great. And there was a long pause before

he responded “Well, no, you have not missed anything, nothing has happened

with that idea.”

Well,

nothing seemed to have happened. I retired

from the State Department and became a law professor at George Washington

University and then was invited

to become the first president of the Iowa Peace Institute in 1988. At the end of 1989 I was in London and I went to call on one of my friends

at the Foreign Office who had been involved in that treaty negotiation. I asked

him if something had happened that I missed

regarding the implementation of this Bills of Rights idea which I thought was

great. And there was a long pause before

he responded “Well, no, you have not missed anything, nothing has happened

with that idea.”

I

said “Well, do you plan to have something happen?” There was again a

very long pause at that point, and finally he said “No”. Then I asked

why he had put that idea into the document in the first place if he did not plan

to do anything about it? He said: “for public relations purposes”. So

here was a government with no intention to pursue one of the articles of an international

treaty that they had signed and registered at the United Nations. I was offended. I am glad to say that in this case it was not

our government, which I also sometimes get offended at, but this was another government.

These were the British government and the Irish government. So a good friend of mine, Joseph Montville,

and I decided that we were going to do something about that. We finally convened at the end of 1990, early

1990 I guess it was, a little group in New

York. We invited two people from Northern Ireland,

one Protestant and one Catholic, one a human right’s lawyer and the other

a peace activist. We sat together for several

days to see if there was something we could do, taking a piece out of this whole

conflict of Northern Ireland, which had been going on for 400 years, to see if

we could make a small step forward, focusing on a Bill of Rights, which we were

told everybody in Northern Ireland wanted to have happen.

These

two men from Northern Ireland

agreed that they would personally draft a Bill of Rights for Northern Ireland. And then we said that I would convene a meeting

at the Iowa Peace Institute in Iowa

to look at that document with a group of experts and give it the kind of status

that was needed. It took them a year to draft that Bill of Rights for Northern Ireland

and they did it in consultation with many people and they found that all of the

five major political parties thought it was a great idea. On December, 1991, we convened just 15 people.

We had eight people from Northern Ireland.

We had the five key members from the five major political parties, a professor

and the two drafters. Then we had the Canadian

Supreme Court Justice, who had written the Bill of Rights for Canada. We had a professor from New Zealand who had written the Bill of Rights

for New Zealand and a few US experts on

human rights and bills of rights.

We

sat together for a week and we went over every aspect and every line of that draft.

We improved it and strengthened it and finally everyone in that room agreed

to the final text. So we had a document that had credibility, we

had done the staff work for the two countries and we were hopeful that something

more would happen.

At

the end of 1992 there was a big conference on Northern

Ireland with England

and Ireland

participating. They set up an ad hoc committee

on the Bill of Rights for Northern

Ireland at that meeting. The only document on the table was our draft

out of Iowa and three of the five members of

political parties who had been in Iowa

were on the ad hoc committee. At the end

of the conference, both England

and Ireland announced to the

world that they supported this draft Bill of Rights for Northern Ireland

and they included it four times in the agreements that came out a few years later.

Thus, as you see, we took a piece of the problem and actually made it happen.

This is an example of what is possible.

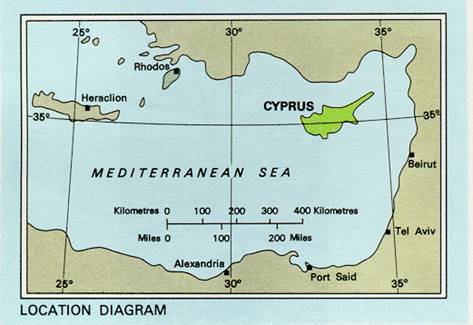

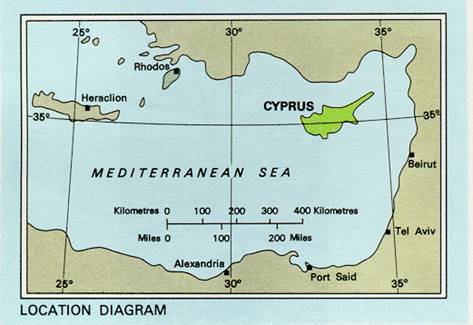

My

second story is about Cyprus. In 1960, as the British Empire was collapsing,

it declared Cyprus

a free and independent nation. They supported

Cyprus’s

joining the United Nations, which it did in 1960. Four years went by peacefully and then there was an attempted coup on the island because

Greece got a little greedy

and wanted to take over all of Cyprus, including the part where the

Turkish Cypriots were living. A lot of ethnic cleansing took place, which is another

word for killing people. The UN Security Council met in an emergency session and

a few months later the UN put in a peacekeeping force. They drew a line down through the capital of

Nicosia, called the Green

Line, and they put peacekeepers on that line. It was a very uneasy peace for the

next ten years.

In

1974 another attempted coup took place, and this time Turkey sent in

35,000 troops and there was a lot more killing.

All the Muslims on the island moved to the North and all the Christians

on the island moved to the South. You could

not cross the Green Line. You could not

send a letter, or make a phone call, to the other side - it was hermetically sealed

in1974. We were invited to that beautiful

island in 1992. Our first project, really,

for my Institute. We were invited by the people in the conflict,

and we only go where we are invited by the people in the conflict.

And we have operated in some 15 countries around the world since 1992.

So we went and we listened. Governments do not know how to listen. And we asked people what their needs were.

Most governments will tell you what your needs are and they will fix them

for you. We do not do that. We go and we listen, we ask what the needs are

and if there is any way that we can fulfill some of those needs as a small, not

for profit, non-governmental organization. That’s

our challenge.

We

decided there was something we could do, we got permission to go to the other

side, and we moved back and forth between the Turkish North and the Greek South,

and we talked to many people. When we take

on a project we make a five year commitment to that project, not a week, not a

month, but five years. And then we called on four Track One entities.

We called on Mr. Denktash who was head of the Turkish-Muslim North.

We called on Mr. Clerides , President of the Greek-Christian South. We called on the United Nations in New York and on its representatives

on the island, and the State Department. We had the same conversation with all four Track

One entities. We said we have been invited

onto the beautiful island by all of those tracks in our multi-track system and

we want to come and respond. We told everyone

that we were going to put on conflict resolution seminars and we invited everyone

from Track One, to attend any seminar they wanted.

We assured them that we are totally transparent, we have no secrets, and

we would love to include Track One members in these training exercises.

Well,

they still did not seem to understand what we were about. So I finally said, “I believe that all

conflict can be resolved. There is no such

thing as an intractable conflict. At some

point in time you are going to sign a Peace Treaty. And all those Turkish soldiers will go home,

and all those peacekeepers on the Green Line will go home, and you will have peace

on your beautiful island - for three weeks. And then someone from the far left or the far

right, who doesn’t want peace but favors war, will throw a bomb or kill somebody.

There will be an act of violence on your beautiful island which will beget

many other acts of violence. But - by that

time we will have trained a critical mass of skilled Cypriots on all levels of

society who have a connection in that village or community where that act of violence

took place. And they will go in there and

contain the conflict. Our goal is to break

the cycle of conflict. If you can break

the cycle of conflict, you can build a peace process.”

They

seemed to understand that. We went back

home, and for fifteen months we worked separately

with the Muslims in the North and the Christians in the South, before we could

bring six from each side together. Finally, we brought those twelve together, after

fifteen months, on the Green Line at the hotel where the UN was staying.

And because they trusted us - and

it is so critical to build a trust relationship - and they had the skills, within

an hour those twelve people bonded, sharing the same desire for peace, and we

made them our steering committee. We were

on that island for the next eight years, not five years as promised, but eight

years, and we and others trained over 2,500 Cypriots together in those eight years. And then we ran out of money and we went home.

They

seemed to understand that. We went back

home, and for fifteen months we worked separately

with the Muslims in the North and the Christians in the South, before we could

bring six from each side together. Finally, we brought those twelve together, after

fifteen months, on the Green Line at the hotel where the UN was staying.

And because they trusted us - and

it is so critical to build a trust relationship - and they had the skills, within

an hour those twelve people bonded, sharing the same desire for peace, and we

made them our steering committee. We were

on that island for the next eight years, not five years as promised, but eight

years, and we and others trained over 2,500 Cypriots together in those eight years. And then we ran out of money and we went home.

In

April of 2003, suddenly the Deputy Prime Minister of the Turkish-Muslim North

opened the gates on the Green Line, and said I want the people from both sides

of the island to come back and forth together.

I want them to live together in peace as they used to. Fantastic statement! Within the first 24 hours, 5,000 people crossed

the Green Line; five thousand! In the next

three months 700,000 people crossed the Green Line. There are only a million people on the island. Nobody was shot, nobody was killed, nobody was

hurt. The whole dynamics of the island

was changed by this one single act of raising the gates. And who raised the gate? One of those six Muslims that we brought to

the table after working with them for the first fifteen months, and then the next

several years. It took ten years, and when

one of these six Muslims finally had the political power to make the decision

to raise the gates, he did it. And that is building peace successfully.

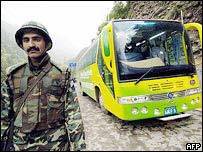

My

third and last example is Kashmir. This has been described by various presidents

as the flashpoint of the world. What happened

was in 1947, when India divided

and Pakistan was created, all

the Muslims were supposed to go to the new state of Pakistan and all the Hindus were to move to India itself.

A major transmigration took place, a very bloody effort unfortunately. But there was one province in the north, called

Jammu and Kashmir, where the Maharaja decided

in the last second to go with India. Each Maharaja under the British

had the right to decide where to go, even though 85% of the population of this

province was Muslim. Thus this unfortunate decision became the root cause of the

conflict in Kashmir.

In

1995 I was visited in Washington

D.C. by two three-star generals and

as you know that’s pretty high up. One

was from India and one was

from Pakistan

and they came together to see me. They

had been invited by the Stimson Center in Washington

D.C. for a month in Washington, they’d just retired from the

military, and they were both career officers.

They heard about our Institute, they came to see me and within the first

two minutes they asked me to solve the Kashmir

problem just like the Soviets earlier. And

I laughed and said “I can’t do that!”

In

1995 I was visited in Washington

D.C. by two three-star generals and

as you know that’s pretty high up. One

was from India and one was

from Pakistan

and they came together to see me. They

had been invited by the Stimson Center in Washington

D.C. for a month in Washington, they’d just retired from the

military, and they were both career officers.

They heard about our Institute, they came to see me and within the first

two minutes they asked me to solve the Kashmir

problem just like the Soviets earlier. And

I laughed and said “I can’t do that!”

But

these men were very serious. They said,

“We have fought two wars against each other over Kashmir. We don’t want to fight a third war, and

we need help. We believe that you as a

small not for profit organization can go in under the radar screen and maybe make

a difference.” Well, I had served in the Middle East

and I knew something about that part of the world. And I said, “Fine, we don’t have any

money, you don’t have any money, but I will put it on our list and see if

something can happen.”

Two

years went by when I was visited by a man from Bombay who had his own not for profit organization

and he had done some work in India/Kashmir and I proposed a new idea to him. I

said, “How would it be if we used our Track Three, the business community,

and see if the business community of first India and then Pakistan

could focus on Kashmir.” Because in 1988 there had been 800,000 tourists

on the Indian side of Kashmir, and then tourism dropped to zero three months later

because of fear, and the whole economy of the province was in despair. He thought

that was a good idea and he invited me to come to Bombay. The day after that it happened that I was visited

by a Pakistani business man who was a Parliamentary leader, brought over by the

State Department’s Visitors Program: same conversation, same invitation.

A week later I got a letter from New

Delhi saying the Chamber of Commerce would like us to be

involved in something there.

Suddenly,

we had three different messages within one week and we decided to raise some money.

Then we went to New Delhi and Bombay in India,

and to Lahore, Pakistan, over the next three years,

to build relationships, to build trust, to make speeches, to talk to people.

And then we organized a program for 28 business leaders in New Delhi for

three days, to focus on Kashmir, and then for 50 business leaders in Lahore, Pakistan

from all over the country a few months later.

The Lt. General who had visited me in Washington

in 1995 opened that seminar and told the participants what a great thing it was

that we were trying to do. And thus began

the first successful steps forward.

At

the same time I was also approached by a Kashmiri from Pakistan who asked

me if we would train political leaders, i.e., politicians from what they call

Azad Kashmir or Free Kashmir. And I said

“Fine” but again no money and they said “we will raise the money”. I was delighted to hear that and asked “when

will we go to your capital?” They

said “No, no, we will bring everyone to Washington,

D.C. because we want them exposed

to the West.”

So

far we have now had four separate trainings for a total of 60 Parliamentary leaders

from Pakistan-Kashmir in Washington

D.C., for a week’s training

each time. The fifth one was planned and

postponed because of the deadly earthquake but we hope to do it in the Fall. We

also were able to build trust on both sides of the line of control of India-Pakistan

and in August of 2004 we brought together ten Kashmiris from India together with ten Kashmiris from Pakistan. That had never been done since the separation

in 1947. Eight of the 20 were women because,

as you all know, it is the women who are the peace builders. The men don’t know that but I know it and

you know it. It was a fantastic time together.

And they bonded, and I thought that was a pretty exciting moment.

Back

up to April 7, 2000: I was invited to make a speech in a refugee camp outside

of Muzaffarabad in Pakistan-Kashmir.

It is pretty tough to address a thousand people who fled from the Indian

side for fear of their lives. I spoke to

them and I had an idea. I said, “You’ve all heard of a politicians’

bus that took place the year before, when the Prime Minister of India took a bus

from New Delhi to Lahore,

Pakistan and met

with the Prime Minister of Pakistan. And

they all remembered that. I said, “I want to start a People’s Bus, just

for the people from divided Kashmir to go back

and forth and visit their divided families on the other side. A People’s Bus is what’s important. It will change the scene. It will build a confidence measure that governments

can appreciate.”

Well,

they thought that was a great idea. So

I came back to Washington

and began to push and I will make a long story very short. On April 7, 2005, the People’s Bus took

place. We’d gotten Track One interested. In my kind of work, we have to move

from Track Two to Track One because they have the political power to open the

gates. And so the two governments, India and Pakistan, did that and that bus then

made a series of thirteen trips back and forth before the earthquake. Now it has

just started up again and they are beginning to move trucks down that particular

path as well.

Well,

they thought that was a great idea. So

I came back to Washington

and began to push and I will make a long story very short. On April 7, 2005, the People’s Bus took

place. We’d gotten Track One interested. In my kind of work, we have to move

from Track Two to Track One because they have the political power to open the

gates. And so the two governments, India and Pakistan, did that and that bus then

made a series of thirteen trips back and forth before the earthquake. Now it has

just started up again and they are beginning to move trucks down that particular

path as well.

We

got some more money and just two months ago we held our second Kashmir dialogue,

on neutral territory, in the Maldive

Islands in the middle of the Indian Ocean,

because Nepal was in trouble

at that point and so was Sri Lanka. And this time, building on the first group,

we brought a total of 27 people together: 14 from Pakistan

and 13 from India,

again 8 women of the 27 were present. And

we had a real meeting of the hearts, and for the first time they agreed to go

public about this meeting, because in the past they were afraid that when they

returned home, they would be subject to criticism and maybe even prison.

But the scene had been changed by a bus, by the earthquake and so particularly

on the Indian side they had increased hope. We

actually had a journalist, one on each side, and they drafted a press release,

and that press release explained what had happened and the journalists had that

printed and wrote articles about that in their respective papers across India and Pakistan. So for the first time, it became public knowledge

that the two sides had met together peacefully and had actually proposed a joint

project to develop a History of Kashmir with both sides of the divided Kashmir

participating.

Last

week I received an e-mail from a man who had read the story in the press from

Indian Kashmir; he is the spokesperson for the government, and he contacted me

and he said, “I want you to come to the Indian side of Kashmir

to carry out conflict resolution training for our government officials.”

It can be done.

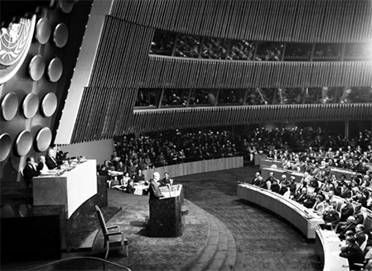

(Picture. President Eisenhower Addressing

United Nations )

)

And

what about the future? I believe that before

the end of this century we will have a world government. Now why do I say that? Is this a dream world or not? I don’t think so. In fact I think that we are a lot closer to

this goal than many people realize this day. The

United Nations Charter, written in 1945, is one of the most powerful documents

in history. And the United States

was the leading drafter, President Roosevelt the leading supporter of that Charter.

It is a great document and I urge you literally at some point to read and to educate

yourself about the process. Unfortunately,

some parts of that Charter have never been put to use because of lack of political

will. There is a whole chapter called Chapter

Six, which talks about peace building and it has wonderful language in there about

how governments should get together and negotiate and arbitrate and try conflict

resolution if they have problems. And then if that does not happen, that chapter

says the Security Council can order any two nations to sit down and negotiate.

And then it goes on to say if this order is given and the two governments

do not do it, then the Security Council will put sanctions on those two governments

to force them to do it. This entire chapter

has never been used since 1945.

Article

43 of the Charter calls for standby military force. Article 45 calls for a standby air force. Article

47 calls for a military staff committee chaired by the joint chiefs of staff of

the five permanent members of the Security Council: France,

Britain, China, Russia

and the United States. None of those articles have ever been used,

imagine that: have never been used!

Why

do we have Rwandas and Darfurs

and Chechnyas? We shouldn’t have those terrible problems. We

should not, as a civilized world, allow those wars to happen. But we are currently lacking the political will

to use the parts of the charter that 192 nations have signed and ratified and

said they would follow, but they have not done so. And so my goal, the next step, is to ensure

that genocide is made an exception to National Sovereignty and that genocide is

declared like it should be in Darfur. But it

has only been called that by Colin Powell in the State Department, no other nation

has done that. Once genocide is declared,

the Security Council should be able to go in and actually end that particular

act of genocide. I want this to be the

first step, to call something Genocide when it is Genocide.

I

also want to see that at some point NATO becomes the military arm of the United

Nations, because I believe the framework for World Government is in existence.

We have already thousands of treaties that bind us in all kinds of ways

together. But NATO can be that military arm for what is

written in Articles 43 and 45. And NATO,

whether you realize it or not, is rapidly expanding beyond its historic confines

of focus on the Soviet Empire alone – because that empire is gone.

NATO’s most recent task has been to do some work in Iraq

and in Afghanistan.

Actually during the earthquake in Kashmir, last

October, NATO sent a thousand troops and military supplies and a thousand tons

of equipment, quickly, to help that particular part of the world. I believe that

there exists already a structure and that we do not have to worry about negotiating

new instruments; all we have to do is have the political will to use the existing

structure and use it to deal with our world problems.

I

also want to see that at some point NATO becomes the military arm of the United

Nations, because I believe the framework for World Government is in existence.

We have already thousands of treaties that bind us in all kinds of ways

together. But NATO can be that military arm for what is

written in Articles 43 and 45. And NATO,

whether you realize it or not, is rapidly expanding beyond its historic confines

of focus on the Soviet Empire alone – because that empire is gone.

NATO’s most recent task has been to do some work in Iraq

and in Afghanistan.

Actually during the earthquake in Kashmir, last

October, NATO sent a thousand troops and military supplies and a thousand tons

of equipment, quickly, to help that particular part of the world. I believe that

there exists already a structure and that we do not have to worry about negotiating

new instruments; all we have to do is have the political will to use the existing

structure and use it to deal with our world problems.

Finally,

I want to talk for a few moments about some personal things that have happened

to me that I cannot explain and I think have to be examined carefully by the world.

I served eight years in the Middle East, four of those years were in Turkey

in the late 50s, and four were in Egypt in the 60s. I became an amateur

archeologist in those eight years, and got very much interested and involved in

the whole process of understanding the history around me in these countries.

I visited the pyramids on many occasions, and of course, the Egyptologists

in Egypt say that the pyramids were built

around 2,600 to 2,250 BC. And I totally

agree with the 5 year old we heard about yesterday evening; he is absolutely on

target.

Those

pyramids could not have been built by the Egyptians; they did not have the know-how.

They did not have even that mathematical symbol pi. Those pyramids are

dramatically placed in alignment with certain star clusters.

They were all three together, they were all covered by beautiful white

marble, whether they had something on top, as was said by the 5 year old, we really

do not know. But those three pyramids could

glisten and be seen for hundreds of thousands of miles. They were not built by the Egyptians; they were

built much, much earlier than that.

Those

pyramids could not have been built by the Egyptians; they did not have the know-how.

They did not have even that mathematical symbol pi. Those pyramids are

dramatically placed in alignment with certain star clusters.

They were all three together, they were all covered by beautiful white

marble, whether they had something on top, as was said by the 5 year old, we really

do not know. But those three pyramids could

glisten and be seen for hundreds of thousands of miles. They were not built by the Egyptians; they were

built much, much earlier than that.

While

I was in Cairo, I did some exploring in the desserts, a few hours outside of Cairo

in something called the Qatar Depression and I came across a Petrified Forest,

petrified logs, petrified wood, and I brought a couple of pieces home. I took one piece about 8 inches long to a stone

cutter in Cairo

and said, “Could you cut it in half so I can have this as a bookend?”

He said it was no problem. I came back

a few days later and he said, “This is the hardest material I have ever seen

in my life. I broke three marble saws on

that one simple three-inch cut.” Indeed, there were forests in the Sahara Desert

a very, very long time ago.

Then

I moved to the Sphinx and try to find out how this actually relates. The Sphinx stands right in front of the three

pyramids, right in line with them. The

sides of the Sphinx have ripple effects. And

there have been in the last several years a number of scientific investigations

and they are absolutely in total agreement that the only way the sides of that

Sphinx could be in that state, would be from downpour, from the rainfall above;

heavy rains over many, many years of time to make that stone appear that way.

So there is no way the Sphinx was built around 2,500 BC as well.

And then in the bottom of the Sphinx, in the foundation, I saw several

stones weighing 70 tons. 70 tons is a lot of weight to bring around with the skills

the Egyptians had at that time.

In

1998, my wife, Christel, and I were in Jerusalem. And they just opened up a corridor a few weeks

before our arrival and we were taken through this tunnel, right next to the Dome

of the Rock and the Wailing Wall. There

was a new opening and we walked through that opening and the guide pointed out

to us several stones weighing 200 tons. Can you imagine today the problems we would

have to move 200 tons anywhere? They were

there and nobody knows who put them there or how they got there. What I am suggesting

is that there are so many things and questions for which we do not know the answers

today and we must always keep an open mind about what hear and what we are talking

about.

I

am concerned about our level of ignorance about the world and I do not understand

why the government of the United States feels that we will panic

if we are told about ETs and UFOs. I mean

everybody in this country has seen Star Wars and ET and movies of all kinds and

TV station reports, which I also happen to watch and enjoy. So nobody is going to panic. I believe that that is a ridiculous argument.

What are they afraid of?

I

am concerned about our level of ignorance about the world and I do not understand

why the government of the United States feels that we will panic

if we are told about ETs and UFOs. I mean

everybody in this country has seen Star Wars and ET and movies of all kinds and

TV station reports, which I also happen to watch and enjoy. So nobody is going to panic. I believe that that is a ridiculous argument.

What are they afraid of?

Why

should we fear anyway because since the ETs have arrived here from outer space

they obviously have the power to destroy us at will and they haven’t done

that, so why should we be afraid of them? It

seems to me that what we should do is to apply what we have learned and practiced

over these years in the whole field of Citizen Diplomacy. And what I want us to do is to apply those skills

to learn how to listen, to learn about fear and how to reduce fear, to learn that

you have to sit down face to face and talk about a conflict if you want to resolve

it. So my word, and my lesson to all of you, is that we welcome strangers in peace.

Thank you.

***

Ambassador John W. McDonald (ret.) is

a lawyer, diplomat, former international civil servant, development expert and

peacebuilder, concerned about world social, economic and ethnic problems. He spent

twenty years of his career in Western Europe and the Middle

East and worked for sixteen years on United Nations economic and social

affairs. He is currently Chairman and co-founder of the Institute for Multi-Track

Diplomacy, in Washington D.C.,

which focuses on national and international ethnic conflicts. He has written or

edited eight books on negotiation and conflict resolution. Ambassador McDonald

holds both a B.A. and a J.D. degree from the University

of Illinois, and graduated from the National War

College in 1967. He was appointed

Ambassador twice by President Carter and twice by President Reagan to represent

the United States

at various UN World Conferences. Main website: http://www.imtd.org/

Ambassador John W. McDonald (ret.) is

a lawyer, diplomat, former international civil servant, development expert and

peacebuilder, concerned about world social, economic and ethnic problems. He spent

twenty years of his career in Western Europe and the Middle

East and worked for sixteen years on United Nations economic and social

affairs. He is currently Chairman and co-founder of the Institute for Multi-Track

Diplomacy, in Washington D.C.,

which focuses on national and international ethnic conflicts. He has written or

edited eight books on negotiation and conflict resolution. Ambassador McDonald

holds both a B.A. and a J.D. degree from the University

of Illinois, and graduated from the National War

College in 1967. He was appointed

Ambassador twice by President Carter and twice by President Reagan to represent

the United States

at various UN World Conferences. Main website: http://www.imtd.org/

***

[Ed.

Grateful thanks to Teri Callaghan who transcribed Amb. McDonald’s conference

speech].

***

http://www.earthtransformation.com

Today

there is no force out there that can do that or has the power to do that. In 1945 when the UN Charter was signed, every

nation in the world, except

Today

there is no force out there that can do that or has the power to do that. In 1945 when the UN Charter was signed, every

nation in the world, except  I

told them that people have fought and died for the right to practice their religion

since time began and I urged them to change the rules. The third non-negotiable issue has to do with

culture. I said you try to deny the ethnicity

of these 70 groups by denying their birth and marriage and death ceremonies, the

clothes they wear, the food they eat, their art, their dance, their music, their

literature. You try to destroy their identity

and they will fight to maintain that identity. I said when you put all three together and you

deny language, religion and culture, you are 100% guaranteed to have conflict,

and killing and death; and you have to change the rules. And the beauty of these three rules is that

they are all man-made. They can all be

changed by the stroke of a pen if the political will is there to do it, and I

urged them to begin that process.

I

told them that people have fought and died for the right to practice their religion

since time began and I urged them to change the rules. The third non-negotiable issue has to do with

culture. I said you try to deny the ethnicity

of these 70 groups by denying their birth and marriage and death ceremonies, the

clothes they wear, the food they eat, their art, their dance, their music, their

literature. You try to destroy their identity

and they will fight to maintain that identity. I said when you put all three together and you

deny language, religion and culture, you are 100% guaranteed to have conflict,

and killing and death; and you have to change the rules. And the beauty of these three rules is that

they are all man-made. They can all be

changed by the stroke of a pen if the political will is there to do it, and I

urged them to begin that process. In

1985, while I was still with the State Department I wrote the book called “Track

Two” or “Citizen Diplomacy”, the first book of its kind and actually

I had a little problem for publication. This

book outlined eight different actions that individuals had taken to help resolve

conflicts in various parts of the world, on their own, as private citizens.

And my boss, when the book was ready for publication, got cold feet.

He didn’t want a book to come out under a State Department label saying

that there are other and new ways of doing business. So he held up publication

for 18 months. One thing about the Foreign

Service is you always get transferred at some point in time. He got transferred after 18 months, and the

day after he got transferred I got the book published.

In

1985, while I was still with the State Department I wrote the book called “Track

Two” or “Citizen Diplomacy”, the first book of its kind and actually

I had a little problem for publication. This

book outlined eight different actions that individuals had taken to help resolve

conflicts in various parts of the world, on their own, as private citizens.

And my boss, when the book was ready for publication, got cold feet.

He didn’t want a book to come out under a State Department label saying

that there are other and new ways of doing business. So he held up publication

for 18 months. One thing about the Foreign

Service is you always get transferred at some point in time. He got transferred after 18 months, and the

day after he got transferred I got the book published.

Well,

nothing seemed to have happened. I retired

from the State Department and became a law professor at

Well,

nothing seemed to have happened. I retired

from the State Department and became a law professor at

They

seemed to understand that. We went back

home, and for fifteen months we worked separately

with the Muslims in the North and the Christians in the South, before we could

bring six from each side together. Finally, we brought those twelve together, after

fifteen months, on the Green Line at the hotel where the UN was staying.

And because they trusted us - and

it is so critical to build a trust relationship - and they had the skills, within

an hour those twelve people bonded, sharing the same desire for peace, and we

made them our steering committee. We were

on that island for the next eight years, not five years as promised, but eight

years, and we and others trained over 2,500 Cypriots together in those eight years. And then we ran out of money and we went home.

They

seemed to understand that. We went back

home, and for fifteen months we worked separately

with the Muslims in the North and the Christians in the South, before we could

bring six from each side together. Finally, we brought those twelve together, after

fifteen months, on the Green Line at the hotel where the UN was staying.

And because they trusted us - and

it is so critical to build a trust relationship - and they had the skills, within

an hour those twelve people bonded, sharing the same desire for peace, and we

made them our steering committee. We were

on that island for the next eight years, not five years as promised, but eight

years, and we and others trained over 2,500 Cypriots together in those eight years. And then we ran out of money and we went home. In

1995 I was visited in

In

1995 I was visited in  Well,

they thought that was a great idea. So

I came back to

Well,

they thought that was a great idea. So

I came back to  )

) I

also want to see that at some point NATO becomes the military arm of the United

Nations, because I believe the framework for World Government is in existence.

We have already thousands of treaties that bind us in all kinds of ways

together. But NATO can be that military arm for what is

written in Articles 43 and 45. And NATO,

whether you realize it or not, is rapidly expanding beyond its historic confines

of focus on the Soviet Empire alone – because that empire is gone.

NATO’s most recent task has been to do some work in

I

also want to see that at some point NATO becomes the military arm of the United

Nations, because I believe the framework for World Government is in existence.

We have already thousands of treaties that bind us in all kinds of ways

together. But NATO can be that military arm for what is

written in Articles 43 and 45. And NATO,

whether you realize it or not, is rapidly expanding beyond its historic confines

of focus on the Soviet Empire alone – because that empire is gone.

NATO’s most recent task has been to do some work in  Those

pyramids could not have been built by the Egyptians; they did not have the know-how.

They did not have even that mathematical symbol pi. Those pyramids are

dramatically placed in alignment with certain star clusters.

They were all three together, they were all covered by beautiful white

marble, whether they had something on top, as was said by the 5 year old, we really

do not know. But those three pyramids could

glisten and be seen for hundreds of thousands of miles. They were not built by the Egyptians; they were

built much, much earlier than that.

Those

pyramids could not have been built by the Egyptians; they did not have the know-how.

They did not have even that mathematical symbol pi. Those pyramids are

dramatically placed in alignment with certain star clusters.

They were all three together, they were all covered by beautiful white

marble, whether they had something on top, as was said by the 5 year old, we really

do not know. But those three pyramids could

glisten and be seen for hundreds of thousands of miles. They were not built by the Egyptians; they were

built much, much earlier than that.  I

am concerned about our level of ignorance about the world and I do not understand

why the government of the

I

am concerned about our level of ignorance about the world and I do not understand

why the government of the  Ambassador John W. McDonald (ret.) is

a lawyer, diplomat, former international civil servant, development expert and

peacebuilder, concerned about world social, economic and ethnic problems. He spent

twenty years of his career in Western Europe and the

Ambassador John W. McDonald (ret.) is

a lawyer, diplomat, former international civil servant, development expert and

peacebuilder, concerned about world social, economic and ethnic problems. He spent

twenty years of his career in Western Europe and the